Assignment L.11.02: Reflection

I rarely propose assignments. I rarely do them. I do not expect an enthusiastic response. That is not the Lichtenberg way. Our way is toss off whatever it may be with only smothered hope. Followed by a smirk. And then walk away quickly.

I propose a structure that may inspire a creative response. I’m mostly interested in whether or not the structure is useful in any and all media or though any and all modes of expression. Need the structure be explicit within the work? Good question. Visible or invisible? Subject or silent support of some other subject? Are we always aware of what stages the supporting mise en scene of our every thought, revery or effort?

The structure is built on reflection. Looking into a mirror and seeing not only oneself but also, behind oneself, another. Another looking perhaps at one’s back or at the reflection of one’s eyes. And so, what may follow? Might one try to look into the eyes of the reflected other to discern what the other sees, to see if the other sees one’s attempt to look? Everything would then circulate about the question: at any moment, does the other share the beam of sight with the one looking? A beam shared though reflected.

You can ignore everything after my initial sketch of the lines of sight, after the first three sentences of the previous paragraph. To imply that a question might reside within this structure is an imposition, I realize. Certainly a possibility within the structure, but not necessary for creative exploitation. Don’t attach anything to it unless it’s useful. You need not let this structure lead to questions of any sort.

A mundane though uniquely modern phenomenon. Mirrors certainly are part of the architecture of mind and self in the modern world. And I say modern (said it twice, now, really three times, heaven help me) fully aware that glassy reflection appears in myth, theology and other pre-Renaissance moments of thought. An aside, this paragraph, a ruffling of an otherwise smooth and unfussy texture. Or a skidding waver of the beam.

It occurs to me to add that, for the purposes of this assignment, I consider philosophy to be a mode of creative expression.

We all have come short

This is from today’s Writer’s Almanac.

Today we celebrate the birthday of dime novelist Ned Buntline (books by this author), born Edward Zane Carroll Judson in Stamford, New York (1813) — probably, but not certainly, on this day. As a boy, he got in a fight with his father and ran away to sea. He started out as a cabin boy, but as a teenager he rescued the drowning crew of a boat, and President Van Buren was so impressed that he appointed the young man a midshipman, a low rank of officer. Some of the other officers refused to eat or socialize with him because he had been a regular sailor. In response, he challenged 13 officers to a duel in one day, and seven of them accepted. He wounded four of them and was completely unhurt himself, and after that, everyone accepted him.

After a few years at sea, he decided to take up writing sensational adventure stories. He took his pseudonym, Ned Buntline, from the “buntline” knot that went at the foot of a square sail. He started out writing about gangs and violence in New York — he had firsthand knowledge of that world, being involved in gang wars himself.

After years of setting his popular dime novels in the seedy underbelly of New York, he took a trip out West, and realized that it was the ideal setting for the type of stories he wanted to tell. He met Buffalo Bill Cody, and adapted his adventures into wildly popular and exaggerated stories, a series called Buffalo Bill Cody — King of the Border Men. It was so successful that he made the stories into a play, Scouts of the Prairie, and he managed to convince the reluctant Buffalo Bill to come play himself in the play. Buffalo Bill and Ned himself were terrible actors, and the critics weren’t impressed — the drama critic for the Chicago Times wrote: “On the whole, it is not probable that Chicago will ever look upon the like again. Such a combination of incongruous drama, execrable acting, renowned performers, mixed audience, intolerable stench, scalping, blood and thunder, is not likely to be vouchsafed to a city for a second time — even Chicago.” A critic for The New York Herald wrote that Buntline played his part “as badly as is possible for any human being to represent it.” But despite the opinions of the critics, Scouts of the Prairie was a commercial and financial hit, and it toured all over the country. Ned Buntline and Buffalo Bill parted ways after that, but Buntline had made the western hero so famous that he was able to open his own show, “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West,” and Bill’s story had set Buntline on his path to earn more money from his writing than any other author in the country.

Buntline’s life was one big adventure, and he didn’t slow down even after he became wealthy and famous. He fought in the Everglades in the Second Seminole War, and was an officer in the Civil War until he was given a dishonorable discharge for drunkenness. He went around preaching temperance despite his own outrageous drinking habits — he interrupted every show of Scouts of the Prairie for a temperance lecture, and he was frequently drunk during those lectures. He was thrashed in public in the streets of New York City by a woman who was the target of gossip in his magazine. He incited several riots. He got in plenty of trouble with women, too — he was married seven times, and was jailed for bigamy. At one point he was flirting with a married teenager named Mary Porterfield. Her husband, Robert, challenged Buntline to a duel, which of course he accepted, and he killed Robert Porterfield. The angry townspeople attempted to lynch Buntline, and in fact they strung him up hanged him from an awning post. At the last minute, his friends cut the rope and he managed to survive.

As Ned Buntline lay dying, he wrote a poem, which ends:

“Counting time by ticking clock,

Waiting for the final shock —

Waiting for the dark forever —

Oh, how slow the moments go,

None but I, me seems, can know

How close the tideless river.”He died in 1886, by which time he had already sent out several false obituaries, further exaggerating his life and claiming that he had been a colonel in the Civil War. At least three of his wives or ex-wives attempted to claim that they were his official widow.

When you read about a life like this, what is your inner reaction?

Indeed.

On a brighter note…

… I believe I may have found a place for the 2012 Annual Meeting.

Hm.

Know, express, reveal, destroy and resurrect.

Umberto Eco: thoughts

From today’s Writer’s Almanac email, two quotes from Umberto Eco:

I have come to believe that the whole world is an enigma, a harmless enigma that is made terrible by our own mad attempt to interpret it as though it had an underlying truth.

…and…

Perhaps the mission of those who love mankind is to make people laugh at the truth, to make truth laugh, because the only truth lies in learning to free ourselves from insane passion for the truth.

Discuss?

In Praise of Procrastination

Protected: Annual Meeting, 12/18/10

Original Katydids and Pan-Dimensional Mice

This essay is necessarily sketchy and incomplete. I write it merely to give everyone a handle on the ideas involved for the Annual Meeting topic, so that you may prepare your deep thoughts, ammunition, references, and cantankerousness beforehand.

1Z0-265

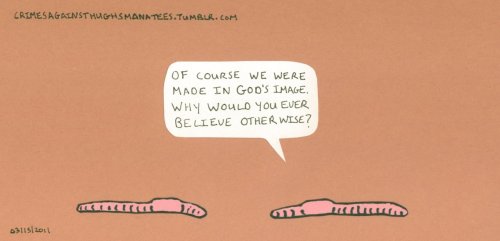

On the Retreat last month, we were sitting in the hot tub the first night and discussing the nature of God and how we understand him/her/them/it/us. I seized upon the metaphor of the katydid, i.e., the pretty little insect who sings and sings, but who has an extremely limited perception of the world around him.

But more than that, the katydid perceives the world around him in ways that we cannot. The main idea was that a) our perception of the universe is as limited as that of the katydid’s; and b) no matter how much we think we understand of the universe, our perception can never be complete, because we will never have the perceptions of the katydid (or the cat, or the dog, etc.).

Fast forward to last week, as I finished reading Forgotten Truth, by Huston Smith. He makes some pretty outrageously recherché claims near the end, and in his epilogue he tries to sidle out of them by claiming that he’s not really reactionary, he’s getting back in touch with the original meaning of the word original. Nowadays, he says, due to our entrapment with scientism (with which argument I can agree), we focus on the “completely new†definition of the word: “He’s so original!â€

But, he says, we should, in our relationship with the universe/God, we should remember what it really means: the source, as in Midsummer Night’s Dream, when Titania bitches to Oberon that the climate change disasters are due to their disagreements: “And this same progeny of evils comes / From our debate, from our dissension; / We are their parents and original.â€

So combine those two ideas: the Artist who creates without a full understanding of his Universe. Or you may go further if you wish.

Our second motif is of course from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. It seems that the Earth is merely a supercomputer constructed for the benefit of a race of pan-dimensional beings to answer the question to Life, the Universe, and Everything. [Actually, of course, it’s seeking the question. We know that the answer is 42.]

In order to operate in our dimension, they insert themselves as mice. Again, from Huston Smith, humans are manifestations of the Eternal. He posits essentially a Great Chain of Being (although not hierarchically arranged as the Elizabethans had it), in which the Levels of Reality go from Terrestrial to Intermediate to Celestial to the Infinite. Likewise, he says, the Levels of Selfhood go from Body to Mind to Soul to Spirit. (He puts Infinite and Spirit in all caps; I shall refrain.)

1Z0-271

So while we may be katydids, we are pandimensional katydids: merely the bottom end of a great slice of the Infinite. We are in fact part of the great Eternal that we yet cannot perceive.

Go.